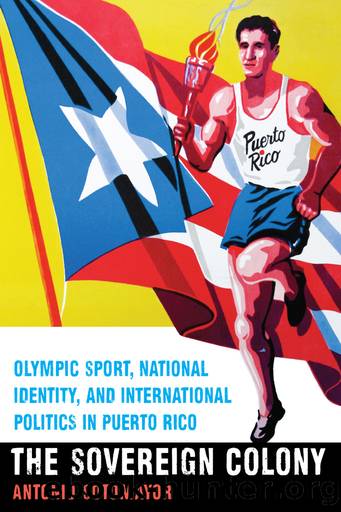

The Sovereign Colony by Antonio Sotomayor

Author:Antonio Sotomayor [Sotomayor, Antonio]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 978-0-8032-8538-5

Publisher: Nebraska

Published: 2018-09-15T00:00:00+00:00

Monagas was not going to let this affront pass, not after the struggle to recognize the COPR, not after his own battle to hold onto power in the COPR, and definitely not given his integral role in the legitimation of sport autonomy in the commonwealth. The position of the USLTA was an indication that the commonwealth did not resolve Puerto Ricoâs colonial relation to the United States. Making the USLTA or the International Lawn Tennis Federation resolution official would have been politically disastrous to both the U.S. and Puerto Rican governmentsâ claims of final decolonization. Moreover such a ruling would place the IOC and the un in a difficult predicament because both had recognized Puerto Rico, the former as separate from the United States, the latter as a decolonized territory.75

Rejection of Puerto Ricoâs Olympic presence, and nationhood, was also internal. Estadista followers were quickly gaining ground in the 1950s, and one of them, Pedro Ramos Casellas, denounced the existence of COPR. In a letter sent to Brundage on September 23, 1959 (the ninety-first anniversary of the Puerto Rican pro-independence uprising against imperial Spain), he averred that Puerto Rico was ânot a nation, never has been a nation and will never be an independent nationâ because the âcompactâ of 1952 affirmed Puerto Ricans as U.S. citizens, as part of the United States.76 He attacked Rolando Cruzâs behavior at the Pan-American Games in Chicago for not accepting his bronze medal in the pole vault unless the Puerto Rican flag was hoisted and the Puerto Rican national anthem played. Ramos Casellas called this act âshamefulâ and demanded an investigation. Brundage responded that the IOCâS recognition of a Puerto Rican National Olympic Committee was given at Puerto Ricansâ request, and he suggested that Ramos Casellas address the COPR directly.77

Still, under Monagasâs leadership, the COPR was perceived by other Latin American nocs as a separate and sovereign Olympic entity. After the Pan-American Games in 1959, Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Chile, Uruguay, Brazil, and Argentina requested a visit from Monagas to evaluate their Olympic track and field programs.78 (Even though Puerto Rico did not win the track and field meets, the team did place above many other Latin American teams.) More important, Monagas was praised as the key figure to help resolve difficulties between Latin American and U.S. delegations. Just as in the 1930s, Puerto Ricoâs Olympic delegation and leadership in the 1950s were still seen as the bridge between two cultures.

Puerto Ricoâs struggle for recognition of its sporting sovereignty was far from over. The fact that some viewed Puerto Ricoâs Olympic participation as unlawful while others viewed it as successful points to the islandâs pervasive colonial Olympism. As in other facets of daily life, colonialism permeated the island and resulted in its colonial sovereignty. Athletic modernization came with a cost: subjugation to an external metropole. Internal bureaucracy, patronage practices, and overarching centralization also hampered the development of institutions. Yet one successful outcome resulted from the development of Olympism in the 1950s: the consolidation of a sporting identity that fueled Puerto Rican national identity.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Six Minutes in Berlin: Broadcast Spectacle and Rowing Gold at the Nazi Olympics by Michael J. Socolow(150)

Scientific Principles of Strength Training: With Applications to Powerlifting (Renaissance Periodization Book 3) by Dr. Mike Israetel Dr. James Hoffmann Chad Wesley Smith(146)

Jailhouse Journalism by James McGrath Morris(117)

Beyond the Final Score: The Politics of Sport in Asia by Victor Cha(98)

The Telegraph Book of the Olympics by Martin Smith(96)

Sport, Globalisation and Identity by Jim O'Brien Russell Holden Xavier Ginesta(93)

The Sovereign Colony by Antonio Sotomayor(92)

Tarnished Rings by Stephen Wenn(91)

Drug Games : The International Olympic Committee and the Politics of Doping, 1960-2008 by Thomas M. Hunt; John Hoberman(83)

How to Watch the Olympics: The Essential Guide to the Rules, Statistics, Heroes, and Zeroes of Every Sport by David Goldblatt & Johnny Acton(74)

Understanding International Sport Organisations: Principles, Power and Possibilities by Lincoln Allison & Alan Tomlinson(73)

Soccer Diplomacy: International Relations and Football since 1914 (Studies in Conflict, Diplomacy, and Peace) by Heather L. Dichter (editor)(70)

The Olympic's Most Wanted™ by Floyd Conner(68)